|

|

|

|

|

|

Portico Books |

|

© 2000-2011 Portico Books |

|

|

First published by The Old Schoolhouse, LLC in the Winter 2010 issue of The Old Schoolhouse Magazine.

Top 10 Tips for Teaching Writing

Writing provides an opportunity for us to communicate with

people we may never meet face to face. Helping children become

effective writers will equip them to share their ideas and their

feelings—and perhaps even influence others.

However, many people—adults and children alike—find writing to

be a stressful challenge. Writing instruction can loom

as an even more daunting task.

Writing can be distressing because it is an extremely complex

process in which people must tend to many tasks simultaneously:

form an idea, put the idea into words, spell the words

correctly, capitalize and punctuate appropriately, and shape

letters (or find them on a keyboard). In addition, while working

on one sentence, the mind is probably racing ahead to consider

the next one!

A key to successful writing—and to

successful writing instruction—is to break the writing

process into manageable parts in order to focus on one step at a

time. This dispels the panic or confusion that may have

paralyzed the overburdened brain. The process approach provides

a way to complete the writing task with a minimum of

frustration.

A word of caution regarding writing

instruction: Teachers often replace the challenge of writing

with the security of worksheets. Completing a worksheet is

quicker and easier than writing a composition, and the worksheet

is easier for a parent or teacher to evaluate. However, in the

vast majority of cases, completing a worksheet is not

writing. A worksheet may help to hone a particular skill,

but unless it allows students to express their own ideas, it

does not require them to write.

The bulk of

language arts time should be spent in genuine

communication—listening, speaking, reading, writing, or

thinking. The best way for young people to improve their writing

skill is to write. They should practice all steps of

the writing process; however, they might not go through the

entire process with each writing experience.

The

following tips for writing instruction apply to writers of all

ages and abilities. Most of the tips relate directly to the

writing process. Tips #1–3, which may not appear to involve

writing instruction, in fact establish a vital foundation on

which to build.

1. From the time your children

are toddlers—or even before—show them that you value

communication. Listen attentively when they talk to

you. Expect them to listen attentively when you talk to them.

When you are communicating something important, be sure you have

eye contact with them. Be sure you are looking at them, and be

sure they are looking at you. Your children's perception of your

attitude toward communication will carry over from listening and

speaking to reading and writing.

2. Do some

writing yourself. This serves a dual purpose. First, it

provides experience with the writing process so that you can be

a more effective guide for your children. Second, it gives you

the opportunity to model writing. If your children see you write

for a variety of purposes, they will understand that you value

writing, and they will begin to identify situations in which

writing will work for them as well.

3. Expose

children to a variety of genres—stories, poems,

non-fiction articles, essays, plays, etc.—both for reading and

for writing. Read to your children, and read with your

children—even when they are able to read independently.

Reading provides excellent preparation for writing. Sometimes a

piece that has been read serves as a direct model for writing.

Other times the influence is subtler. All aspects of material

read—content, structure, sentence patterns, imagery,

sound—remain in the storehouse of the mind, often below

consciousness but available for use, perhaps in a composition.

Students should write in every subject, not just in English

class. Writing provides a chance for students to demonstrate

their knowledge, expand their understanding, and clarify their

thinking. Following the same writing process in all subjects

will help students see writing not as a meaningless drill but as

a tool that will serve them well in a variety of situations

throughout their lives.

4. Help children think

of—and keep track of—their ideas for writing. Thinking

of something to write about often becomes a writer's first

difficulty. Writers can bypass this obstacle if they capture

ideas when they occur instead of waiting until ideas are needed.

When something sparks your child's interest, you might say, "You

might want to write about that sometime."

Your child

needs to keep track of these ideas. They can be kept on separate

note cards or listed on a sheet of paper. A loose-leaf notebook

is perhaps the ideal format, allowing ideas to be categorized

yet easily moved. A loose-leaf notebook also easily accommodates

pages that have been printed on a computer or acquired from

other sources.

In addition to lists of possible writing

topics (perhaps with a few notes for development), an "idea

book" may include intriguing questions, observations,

descriptions, conversations, opinions, etc. Keeping an idea book

sharpens writers' awareness of the world around them, records

thoughts and experiences, and preserves ideas for future use.

5. Help children find an audience for their

writing. Writing is more meaningful when it is genuine

communication rather than a mere exercise. There are many

opportunities for children to share their writing with their

family and their community. They can write letters, stories for

younger children, contest entries. They might write some pieces

on special paper, enhance them with a drawing or photograph,

and/or frame them or bind them into a book. Such treatments show

high regard for the work and invite a larger audience.

On occasions when writing is "just an assignment," have children

write with a specific audience and purpose in mind so that they

at least imagine an audience beyond the teacher.

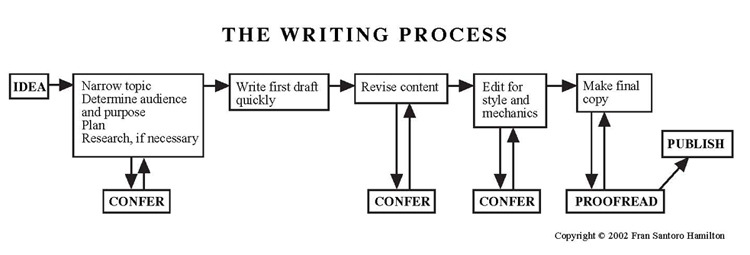

6. Provide opportunities for children to get feedback throughout the writing process. Professional writers regularly consult others, yet adults often make the writing task more difficult for children by requiring them to "do it all themselves." The flow chart below shows four points at which a writer would benefit from feedback. The "responder" in a writing conference could be a parent or teacher, a sibling, a peer. Writers should learn to select people who would be most helpful in specific situations.

|

| A key to successful writing—and to successful writing instruction—is to break the writing process into manageable parts in order to focus on one step at a time. Each pair of vertical arrows represents a loop that may be traveled repeatedly. A writer may confer many times—with several people—before he or she is ready to move on to the next stage of the writing process. |

The process for obtaining feedback differs at various points of the writing process. In the planning stage the main job of the responder is to listen and question. The writer should do most of the talking, since talking provides excellent rehearsal for writing. The responder's questions show the writer which parts of the composition need further development or clarification.

After the first draft has been written, the responder helps

the writer know what comes across from the composition. It works

well for the writer to read the composition aloud and for the

responder to "tell back" what he or she has heard. This keeps

the focus on content rather than mechanics. A reader's feedback

is invaluable in helping the writer improve the composition. A

writer who asks open-ended questions about specific parts of the

composition will encourage additional feedback; however, a

writer who becomes defensive will discourage suggestions. A

writing conference is likely to be most productive when the

writer knows what specific help he or she needs at that time.

Although a writer may confer with many people, ultimately he or

she is the one who must decide which changes to make.

7.

Free children to write their first draft without

worrying about correctness of anything—spelling, capitalization,

punctuation, sentence structure, vocabulary. They

should write their first draft very quickly, and that draft can

be very rough. The important thing is to unleash the flow of

ideas. Some writers find it helpful to dictate their first

draft.

Remind your children that a first draft need not be written in sequence. The introduction, in fact, is often one of the most difficult parts of a composition to write. Encourage students to write any section they feel ready to write. Using a different sheet of paper for each part (or using a word processor) will simplify assembly of the finished piece.

Young writers—like professional writers—may prefer to write at a certain time of day or in a particular place. They may prefer a certain kind of paper (small pages, for example, may seem less intimidating). They may prefer a particular kind of writing implement, or they may prefer to compose directly on a word processor. Encourage young writers to experiment with various techniques in order to find what works best for them.

8. Help children succeed with editing. After

the content of a composition is established, a writer's focus

turns to editing (making mechanical corrections, such as

capitalization, punctuation, and spelling). Have realistic

expectations. Hold young children responsible for applying basic

rules they have studied, such as capitalizing the first word of

a sentence and using appropriate end punctuation. Add new

responsibilities as children learn new concepts.

Provide

resources, such as a dictionary, an

English handbook, and

thesaurus, so that young writers can easily find the information

they need in order to use English correctly. Remind them to use

their computer's spell-check feature—but not to rely on it

completely.

Many writers—especially those who find

mechanical correctness challenging—may benefit from subdividing

the editing step, focusing on one skill at a time. For example,

a writer may start by checking to see if each sentence is

complete. Then he or she may check to see if each sentence

starts with a capital letter. Editing may continue with checking

end punctuation, subject-verb agreement, and spelling—checking

each skill throughout the composition.

Editing should

continue until the writer has checked the composition for each

skill and has gone through the composition at least twice

without making any changes.

9. Respond to

children's writing as a reader before you respond as a teacher

or critic. Respond to the content of a composition so

that writers know their message was received. For example, if

the writer has described his or her grandmother's kitchen, you

might say something like "I can tell that Nana's kitchen is a

very special place to you."

As you begin to evaluate the

writing, again respond first to the content rather than the

mechanics. Take time to tell the writer what was done well.

A natural way to do this is to be specific about what made the

content effective. You could say, for example, "You've described

the sights and sounds—and smells!—so vividly that I felt I was

there myself." After pointing out several things that have been

done effectively, point out two or three aspects of content that

the writer seems ready to learn. Don't try to point out

everything that could be improved. The writer won't remember all

you say and will only become discouraged.

Follow the

same pattern for mechanical skills: Point out things that were

done well, focus on a few skills for instruction, and point out

additional strengths. Sometimes your questions can help the

writer find and correct errors. You might say, for example, "You

have this word spelled two different ways. Which one is right?"

or "Which word in this line should you capitalize?"

Keeping a list of writing skills taught will help you remember

which skills you can expect the child to apply correctly and can

also help you and the child see progress.

10. Make writing enjoyable for both you and your

children. Children are more likely to enjoy writing

when they understand the value of communication and can share

ideas they care about. They are more likely to enjoy writing

when frustration is minimized.

Think about

activities that you enjoy. The more you enjoy them, the more you

do them—and the better at them you become. Writing works this

way, too. Students who enjoy writing will be caught in an upward

spiral of writing success. They will have a tool that will serve

them well throughout their lives.

Hands-On English

Hands-On Sentences

|

View Cart/Checkout |

| Buy Hands-On English, the Activity Book (Reproducible Edition), and Hands-On Sentences for $50.00 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|